Sound Travels

by Thom Jurek

In his sixth decade as a professional musician, Jack DeJohnette has established himself as a musical chameleon. He's led bands and recorded and performed with an array of jazz legends as well as funk and pop artists. DeJohnette has even made new age music listenable with Peace Time and Music in the Key of Om (the latter won him a Grammy). And he has always cultivated and acted on his deep, abiding interest in indigenous musics from Latin America and Africa. Sound Travels is his first recording of new material since 2009's Music We Are. True to form, DeJohnette, who plays drums and piano here, ranges widely. The disc begins with the brief "Enter Here," a grounded yet ambitious offering with the sound of a resonating bell that gives way to DeJohnette's lilting solo piano. "Salsa for Luisto" features the percussionist Luisto Quintero playing grooved-out, modern Afro-Cuban son. Esperanza Spalding is the upright bassist in the band, and on this track, she sings alongside Ambrose Akinmusire's trumpet and Lionel Loueke's guitar. DeJohnette plays piano and drums. This salsa is of the earthier yet breezier Caribbean variety. It's lovely. Just as quickly, things shift into down-home New Orleans-style funky blues with Tim Ries on soprano and tenor saxophones. Bruce Hornsby appears on vocals singing about not surrendering in the face of disaster more soulfully than on any of his own records. Loueke's unique guitar style makes this track sound more like the Band than Allen Toussaint, though Wardell Quezergue's ghost inhabits the horn chart. "New Music" is modern, modal post-bop with Middle Eastern overtones. It features fine traded solos by Ries on soprano and Akinmusire. Township jazz crossed with Latin groove is the bedrock for "Sonny Light," with Loueke's lyric solo being the tune's centerpiece as DeJohnette finds a perfect space to comp behind him and enhance the guitar's presence. The two horns and Quintero's hand drums weave a wonderful, rhythmic lyricism around the pair. The title track is an exercise in rhythm from DeJohnette, Loueke, Quintero, and Spalding (who really drives this track and shines brightly on the album as a whole). "Oneness" is a sparse and moving ballad played by DeJohnette and Quintero, backing vocalist Bobby McFerrin. The song feels deeply indebted to Milton Nascimento's excellent mid-'70s work. The set's longest cut is "Indigo Dreamscapes," a breezy, midtempo, fingerpopping Latin number. DeJohnette's piano work alongside Ries' tenor create an irresistible harmonic progression even when they move the tune toward straight-ahead jazz, then walk it back. The closer, "Home," is another languid, crystalline solo piano piece that is the bookend to "Enter Here." It's quiet, reverent, warm, and inviting, and it pays an indirect homage to Abdullah Ibrahim's South African style. Sound Travels is a current, understated, well-disciplined glimpse into DeJohnette's current musical world view, which is worth celebrating for its own sake.

Jacques Loussier Trio

Samuel Blaser

by Thom Jurek

In his sixth decade as a professional musician, Jack DeJohnette has established himself as a musical chameleon. He's led bands and recorded and performed with an array of jazz legends as well as funk and pop artists. DeJohnette has even made new age music listenable with Peace Time and Music in the Key of Om (the latter won him a Grammy). And he has always cultivated and acted on his deep, abiding interest in indigenous musics from Latin America and Africa. Sound Travels is his first recording of new material since 2009's Music We Are. True to form, DeJohnette, who plays drums and piano here, ranges widely. The disc begins with the brief "Enter Here," a grounded yet ambitious offering with the sound of a resonating bell that gives way to DeJohnette's lilting solo piano. "Salsa for Luisto" features the percussionist Luisto Quintero playing grooved-out, modern Afro-Cuban son. Esperanza Spalding is the upright bassist in the band, and on this track, she sings alongside Ambrose Akinmusire's trumpet and Lionel Loueke's guitar. DeJohnette plays piano and drums. This salsa is of the earthier yet breezier Caribbean variety. It's lovely. Just as quickly, things shift into down-home New Orleans-style funky blues with Tim Ries on soprano and tenor saxophones. Bruce Hornsby appears on vocals singing about not surrendering in the face of disaster more soulfully than on any of his own records. Loueke's unique guitar style makes this track sound more like the Band than Allen Toussaint, though Wardell Quezergue's ghost inhabits the horn chart. "New Music" is modern, modal post-bop with Middle Eastern overtones. It features fine traded solos by Ries on soprano and Akinmusire. Township jazz crossed with Latin groove is the bedrock for "Sonny Light," with Loueke's lyric solo being the tune's centerpiece as DeJohnette finds a perfect space to comp behind him and enhance the guitar's presence. The two horns and Quintero's hand drums weave a wonderful, rhythmic lyricism around the pair. The title track is an exercise in rhythm from DeJohnette, Loueke, Quintero, and Spalding (who really drives this track and shines brightly on the album as a whole). "Oneness" is a sparse and moving ballad played by DeJohnette and Quintero, backing vocalist Bobby McFerrin. The song feels deeply indebted to Milton Nascimento's excellent mid-'70s work. The set's longest cut is "Indigo Dreamscapes," a breezy, midtempo, fingerpopping Latin number. DeJohnette's piano work alongside Ries' tenor create an irresistible harmonic progression even when they move the tune toward straight-ahead jazz, then walk it back. The closer, "Home," is another languid, crystalline solo piano piece that is the bookend to "Enter Here." It's quiet, reverent, warm, and inviting, and it pays an indirect homage to Abdullah Ibrahim's South African style. Sound Travels is a current, understated, well-disciplined glimpse into DeJohnette's current musical world view, which is worth celebrating for its own sake.

Jacques Loussier Trio

Schumann/ Kinderszenen - Scenes From Childhood

by Alex Henderson

Over the years, third stream music has been criticized in both the jazz and Euro-classical worlds. Jazz snobs have argued that if a jazz musician is playing something by Beethoven or Chopin, he/she can't possibly maintain an improviser's mentality; classical snobs will argue that great classical works need to be played exactly as they were written, and that jazz artists can't possibly do the compositions of Schubert, or Debussy justice if they improvise. But thankfully, Jacques Loussier hasn't paid attention to the naysayers in either the jazz or classical worlds, and after all these years, the French pianist (who turned 76 in 2010) is still taking chances. This 2011 release finds Loussier putting his spin on "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)," which German romanticist Robert Schumann (b. 1810, d. 1856) composed in 1838. Schumann turned 28 that year, and he wrote that nostalgic, 13-song work in memory of his childhood. Loussier (who forms an acoustic piano trio with bassist Benoit Dunoyer de Segonzac and drummer André Arpino) performs "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" in its entirety, and he approaches it not as European classical music, but as acoustic post-bop jazz. Thankfully, "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" is appropriate for Loussier, who maintains the 13 songs' nostalgic outlook but does so in a consistently jazz-oriented fashion. Loussier sounds like he is fondly remembering his own childhood, which came about long after Schumann's. Indeed, Loussier was born in 1934, which was 96 years after "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" was composed and 78 years after Schumann's death; Loussier grew up surrounded by a lot of music and technology that didn't exist when Schumann was a kid. But the more things change, the more they stay the same and nostalgia continues to inspire musicians today just as it did in Schumann's pre-jazz, pre-electricity, pre-records time. This 49-minute CD is among Loussier's creative successes; his experimentation hasn't always worked, but it works impressively well for him on this imaginative interpretation of "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)."

by Alex Henderson

Over the years, third stream music has been criticized in both the jazz and Euro-classical worlds. Jazz snobs have argued that if a jazz musician is playing something by Beethoven or Chopin, he/she can't possibly maintain an improviser's mentality; classical snobs will argue that great classical works need to be played exactly as they were written, and that jazz artists can't possibly do the compositions of Schubert, or Debussy justice if they improvise. But thankfully, Jacques Loussier hasn't paid attention to the naysayers in either the jazz or classical worlds, and after all these years, the French pianist (who turned 76 in 2010) is still taking chances. This 2011 release finds Loussier putting his spin on "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)," which German romanticist Robert Schumann (b. 1810, d. 1856) composed in 1838. Schumann turned 28 that year, and he wrote that nostalgic, 13-song work in memory of his childhood. Loussier (who forms an acoustic piano trio with bassist Benoit Dunoyer de Segonzac and drummer André Arpino) performs "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" in its entirety, and he approaches it not as European classical music, but as acoustic post-bop jazz. Thankfully, "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" is appropriate for Loussier, who maintains the 13 songs' nostalgic outlook but does so in a consistently jazz-oriented fashion. Loussier sounds like he is fondly remembering his own childhood, which came about long after Schumann's. Indeed, Loussier was born in 1934, which was 96 years after "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)" was composed and 78 years after Schumann's death; Loussier grew up surrounded by a lot of music and technology that didn't exist when Schumann was a kid. But the more things change, the more they stay the same and nostalgia continues to inspire musicians today just as it did in Schumann's pre-jazz, pre-electricity, pre-records time. This 49-minute CD is among Loussier's creative successes; his experimentation hasn't always worked, but it works impressively well for him on this imaginative interpretation of "Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood)."

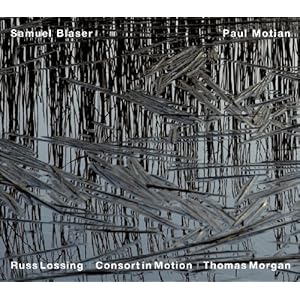

Samuel Blaser

Consort In Motion

By Tim Niland

This is a chamber jazz album filled with hushed tones and thoughtfully designed improvisations between Samuel Blaser on trombone, Russ Lossing on piano, Thmoas Morgan on bass and Paul Motian on drums. The interaction between between Blaser's delicately smeared and articulated trombone and Motian's minimalist percussion creates a quiet, intimate album that requires and concentration and contemplation. “Si Dolce è l'Tormento" and “Reflections on Vespro della Beata Vergine" nudge the tempos slightly up a little bit, engaging the band into full improvisation and interpretation of the themes and melodies.

Geri Allen

A Child Is Born

by William Ruhlmann

Christmas albums tend to be a blend of the traditional and familiar with the style of the recording artist, and jazz pianist Geri Allen's A Child Is Born is no exception. Allen has a technically proficient, often elaborate style as a pianist, and she uses it in her evocations of Christmas carols and hymns. There is a slight nod to Ethiopia in the brief versions of "Imagining Gena at Sunrise" and "Imagining Gena at Sunset," as well as the cover art of a black Madonna and child by Kabuya Pamela Bowens, and Allen occasionally employs a Fender Rhodes electric piano or even a Hohner clavinet for unusual effects, notably on her original "God Is with Us" (a musical setting of the Biblical passage Matthew 1:23). Most of the time, however, she takes on tunes known by most Western listeners, playing the melodies in strong right-hand statements backed by often contrasting left-hand rhythms on acoustic piano. Then, she takes off into complex improvisations that only touch back now and then to the melodies. Her playing sometimes has a new age quality, like George Winston in a slightly jazzier mode. So, this is a holiday collection for the more adventurous jazz piano fan, rather than for someone looking for a safe, warm, and fuzzy set of jazzed-up Christmas tunes.

Dave Liebman & Richie Beirach

Unspoken

It's one thing for individual artists' voices to be instantly recognizable, another thing entirely when a readily identifiable language evolves amongst them, one that's absent when they're apart. There's no mistaking the bop-rooted expressionism that saxophonist Dave Liebman imbues with oblique lyricism, whether with his longstanding group on Turnaround: The Music of Ornette Coleman (Jazzwerkstatt, 2010) or in a new collection of largely old friends on Five on One (Pirouet, 2010). Nicknamed "The Code," pianist Richie Beirach's personal marriage of jazz vernacular with that of classical composers including Béla Bartók, Alexander Scriabin and Anton Webern dates back to solo recordings such as Eon (ECM, 1975) through recent release Round About Bartók (ACT, 2001). But when The Code gets together with 2011 NEA Jazz Master Liebman, something special happens—something that transcends individuality and enters the realm of collective idiom.

Collaborating frequently over the decades in groups such as Lookout Farm and Quest, geography has largely kept them apart since the mid 1990s until a reformed Quest—on Redemption (Hatology, 2007) and Re-Dial (OutNote, 2010)—and Beirach's recent retirement from teaching in Germany seems to have created more opportunities for these two soul brothers to work together. KnowingLee (OutNote, 2010) took their longstanding duo in a different direction with the addition of saxophonist Lee Konitz, but as undeniably fine as that set was, Unspoken represents a welcome return to the unadorned format first heard on the criminally out-of-print Forgotten Fantasies (A&M, 1977).

Nearly 35 years later, the language that Liebman and Beirach have been honing has become nothing if not more recondite. Even when tackling an overworked but deserving chestnut such as Jerome Kern's "All the Things You Are," the familiar melody is couched in the pianist's expansive reharmonization, becoming an ever-present but tenuous thread at constant risk of unraveling. But it's the opening "Invention"—Beirach's arrangement of Aram Khatchaturian's "Adagio," from the ballet Gayaneh, written in 1942 but most popularized by film director Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—that speaks to this duo's remarkable empathy, as the pianist's sustaining introductory notes create a soft landscape over which Liebman's soprano slowly moves towards its equally recognizable theme. Time—as is true with everything about this duo—is fluid, allowing the music to breathe with rarely paralleled freedom and unconscious unity of intent.

Beirach's originals such as "Awk Dance"—with a groove that only the most temporally secure are apt to find, made all the more difficult for shifting in and out of double time—contrast with "Tender Mercies," described by the saxophonist as one of his "simplest ballads" but, traveling from dark dissonance to brooding beauty, seems anything but, beyond the relatively limited range of Liebman's wooden flute.

The saxophonist's closing medley best describes the breadth of this duo, as Beirach channels Olivier Messiaen with a touch that's both delicate and firm on "Hymn for Mum," before Liebman enters equally elegantly, switching to tenor for an a capella intro to "Prayer for Mike" that, in its visceral wails and multiphonic bursts, feels more like catharsis, though it does settle into a more plaintive tone when Beirach reappears.

A paradox of form and freedom, angst and calm, and fire and, if not exactly ice, then at least cool, Unspoken refers, no doubt, to the direct and uncanny line of communication built between Liebman and Beirach over the course of nearly 50 years, where no words need be said to create a language that speaks volumes.

Tracks:

Invention; All the Things You Are; Ballad 1; Awk Dance; New Life; Waltz for Lenny; Tender Mercies; Transition; Hymn for Mom/Prayer for Michael.

Richie Beirach: piano; Dave Liebman: tenor and soprano saxophones, wood flute

Richie Beirach: piano; Dave Liebman: tenor and soprano saxophones, wood flute

No comments:

Post a Comment